The Indigenous World 2024: Costa Rica

The eight Indigenous Peoples that inhabit the country make up 2.4% of the population. Seven of them are of Chibchense origin (the Huetar in Quitirrisí and Zapatón; Maleku in Guatuso; Bribri in Salitre, Cabagra, Talamanca Bribri and Këköldi; Cabécar in Alto Chirripó, Tayni, Talamanca Cabécar, Telire and China Kichá, Bajo Chirripó, Nairi Awari and Ujarrás; Brunca in Boruca and Curré; Ngöbe in Abrojos Montezuma, Coto Brus and Conte Burica, Alto de San Antonio and Osa; and Brörán in Térraba) and one of Mesoamerican origin (the Chorotega in Matambú). According to the 2010 National Census, just over 100,000 people are recognized as Indigenous.

Although 7% of the national territory (3,344 km²) is taken up by 24 Indigenous territories, a large part of this area has been invaded by non-Indigenous occupants: 52.3% of the Bribri area has been invaded in Këköldi, 53.1% in Boruca, Brunca territory, 56.4% in Térraba, belonging to the Brörán people, 58.7% in Guatuso belonging to the Maleku people and 88.4% in Zapatón, Huetar territory.[1]

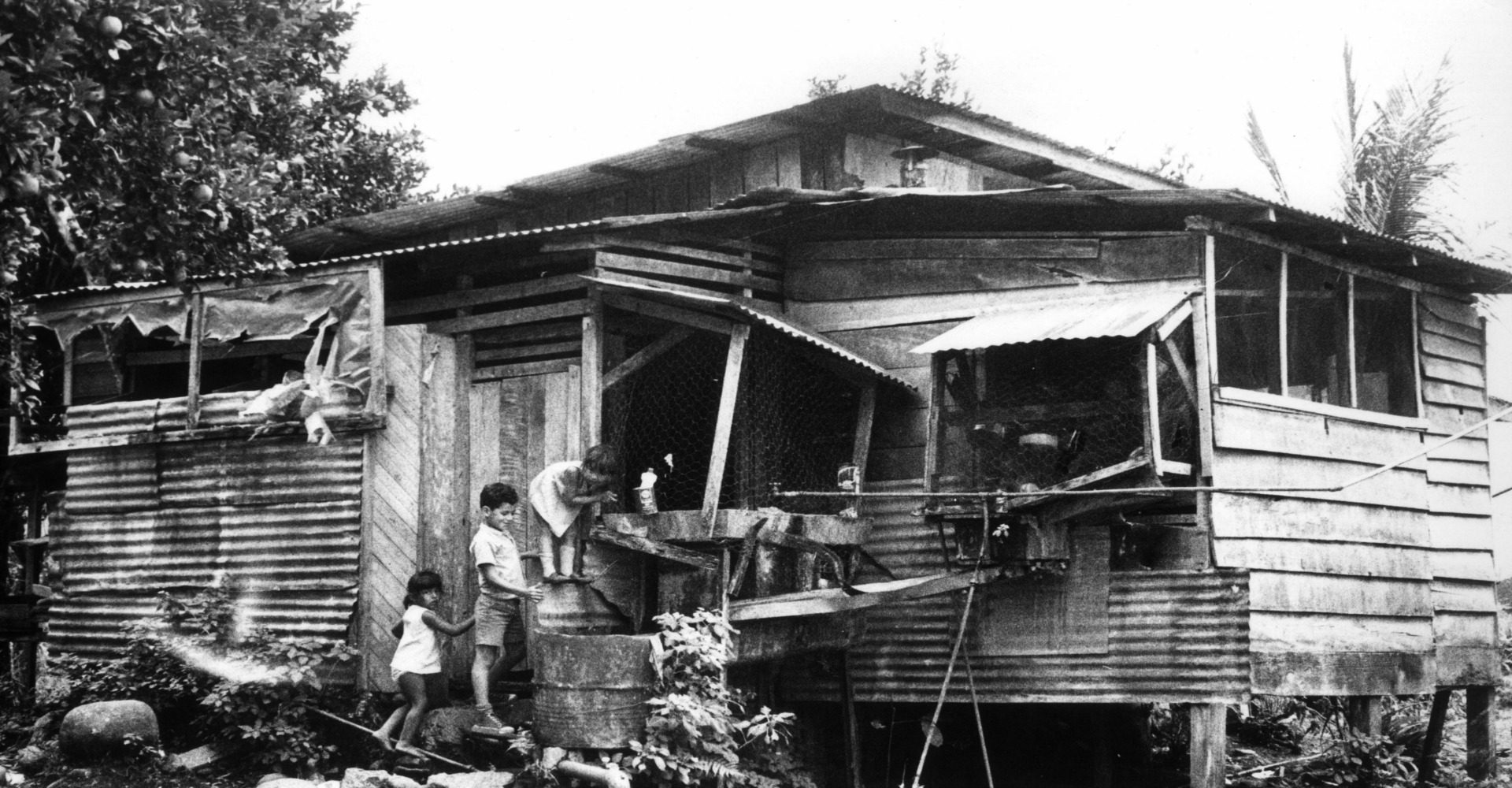

In the country generally, 20% of the population lives below the poverty line; in the case of Indigenous Peoples, however, the figures are alarming: Cabécar 94.3%; Ngöbe 87%; Brörán 85.0%; Bribri 70.8%; Brunka 60.7%; Maleku 44.3%; Chorotega 35.5% and Huetar 34.2%.[2]

Costa Rica ratified ILO Convention 169 in 1993 and added recognition of its multicultural nature to the Constitution of the Republic. Even so, the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous Peoples indicates that “Although article 1 of the Constitution stipulates that Costa Rica is a multi-ethnic and multicultural State, it does not recognize the existence of the [I]ndigenous [P]eoples”.[3]

Indigenous Law 6,172 of 1977 recognized Indigenous organizations, establishing the legal status of Indigenous Peoples, mechanisms to prevent the appropriation of land by non-Indigenous persons, and expropriation and compensation procedures and funds. As of 20 December 2023, however, this had still not been implemented.[4] Quite the contrary, the State has tolerated the invasion and dispossession of Indigenous lands by local landowners and politicians. Indigenous organizations have been demanding regularization of the land for decades. Slowness in the studies and a lack of political will to evict illegal occupants led to the emergence of a land recovery movement that has been evicting squatters since 2011.

A regulation subsequent to the Indigenous Law imposed an entity foreign to the Indigenous Peoples’ traditional power structures, the Integral Development Associations (ADI), under the supervision of the National Directorate of Community Development, a body that does not have the capacity to understand Indigenous rights or an intercultural approach. For the Special Rapporteur, “as imposed State institutions that report to the executive branch, [they] are not suited to guaranteeing representation for [I]ndigenous [P]eoples, which have their own system of government.” [5]

Among the Indigenous organizations that enjoy legitimacy and act in defence of their rights are the Mesa Nacional Indígena de Costa Rica, the Frente Nacional de Pueblos Indígenas (Frenapi), the Red Indígena Bribri-Cabécar, the Asociación Ngöbe del Pacífico, the Asociación Regional Aborigen del Dikes, the Foro Nacional de Mujeres Indígenas, the Movimiento Indígena Interuniversitario and the Coordinadora Lucha Sur (CLSS), a grouping of Indigenous Peoples' organizations and peasant associations.

This article is part of the 38th edition of The Indigenous World, a yearly overview produced by IWGIA that serves to document and report on the developments Indigenous Peoples have experienced. The photo above is of an Indigenous man harvesting quinoa in Sunimarka, Peru. This photo was taken by Pablo Lasansky, and is the cover of The Indigenous World 2024 where this article is featured. Find The Indigenous World 2024 in full here

Territorial rights of Indigenous Peoples

The 1977 Indigenous Law

...emphasizes, on the one hand, the Indigenous right to land, recognizing their reservations and declaring them imprescriptible, inalienable, non-transferable and exclusive to the Indigenous people, ordering the immediate eviction – without compensation – of illegal invaders and the expropriation of good faith possessors.[6] But, at the same time, the State reserves the exclusive right to the rational exploitation of its forests and prohibits the Indigenous people from changing the land use in those areas. The letter of this law, in terms of defending the right to their lands, continues to be unfulfilled as numerous studies on the historical advance of the illegal invasion of lands within Indigenous territories point out. The State has not proceeded to expropriate the previous occupants in good faith nor to evict the illegal invaders, whose numbers continue to increase.[7]

Moreover, the invaders have opted for a strategy of judicializing the territorial conflict,[8] taking their cases to court in order to defer solutions. The Rural Development Institute (INDER), responsible for regularizing the Indigenous territories, thus cannot set a deadline for the goal of recovering the Indigenous lands because the process is being held up in the courts. This strategy is, however, beginning to encounter setbacks.[9]

There is a significant gap between legal recognition of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and the effective enforcement of these rights in almost all territories. A lack of land titling, a clear responsibility of the State, lies at the root of many conflicts. The following are the 24 Indigenous territories recognized by the Costa Rican State, although they have been largely invaded by non-Indigenous people.

Costa Rica’s Indigenous territories, by people and administrative territorial division[10]

|

People |

Territory |

Area[11] (ha) |

Province |

|

Bribri |

Talamanca Bribri |

43,690 |

Limón |

|

Bribri and Cabécar |

Këköldi |

3,538 |

|

|

Bribri |

Salitre |

11,700 |

Puntarenas |

|

Bribri |

Cabagra |

27,860 |

|

|

Cabécar |

Talamanca Cabécar |

22,729 |

Limón |

|

Cabécar |

Telire |

16,260 |

|

|

Cabécar |

Tayni |

16,216 |

|

|

Cabécar |

Nairi Awari |

5,038 |

Cartago |

|

Cabécar |

Alto Chirripó |

74,687 |

Cartago |

|

Cabécar |

Duchí Ñak (Bajo Chirripó) |

19,710 |

Cartago and Limón |

|

Cabécar |

Ujarrás |

19,040 |

Puntarenas |

|

Cabécar |

China Kichá |

1,100 |

San José |

|

Ngöbe |

Abrojos Montezuma |

1,480 |

Puntarenas |

|

Ngöbe |

Altos de San Antonio |

1,262 |

|

|

Ngöbe |

Osa |

2,757 |

|

|

Ngöbe |

Conte Burica |

11,910 |

|

|

Ngöbe |

Coto Brus |

7,500 |

|

|

Brunca |

Boruca |

12,470 |

Puntarenas |

|

Brunca |

Yimba Cájc (Rey Curré) |

10,620 |

|

|

Huetar |

Zapatón |

2,855 |

San José |

|

Huetar |

Quitirrisí |

3,538 |

|

|

Brörán |

Térraba |

9,355 |

Puntarenas |

|

Maleku |

Guatuso |

2,743 |

Alajuela |

|

Chorotega |

Matambú |

1,710 |

Guanacaste |

|

Total |

329,768 |

Persistent barriers to Indigenous self-determination

The draft Law on the Autonomous Development of the Indigenous Peoples of Costa Rica, tabled in 1994, has still not been enacted 29 years later. The most controversial aspect of this law is the discontinuation of the National Commission for Indigenous Affairs (CONAI) and the Integral Development Associations, which are perceived by the Indigenous organizations as parastatal structures being used as substitutes for legitimate forms of Indigenous government.

In addition, it is important to note the State’s serious deficiency in terms of information management and data publication in Costa Rica. The publication of the 2020 census, conducted in 2021, processed in 2022 and whose results were released by the National Institute of Statistics and Census (INEC) in 2023, does not include information on Indigenous Peoples. INEC reports that they have not yet processed this data, an unacceptable situation for the Indigenous Peoples, who are once again rendered invisible.[12]

Indigenous movement for territorial recovery continues

In the canton of Sixaola, on the border with Panama, there is a cross-border Ngöbe population, estimated at 10,000 people, who have no territory in which to anchor their culture.[13] They are forced into a perpetual migration for work between the two countries, selling their labour in agro-industrial companies where they suffer mistreatment and abuse.[14] In March, a group of Ngöbe leaders met with the Vice-Minister for Peace, who promised to allocate them a farm through INDER's endeavours. It is still unknown which farm, where it will be located, or even if there has been any follow-up on this still unfulfilled promise.[15]

In the recovered territories in Salitre, Térraba, Cabagra, China Kichá and Guatuso, the Indigenous communities are embarking on a valuable process of cultural and environmental restoration, with strong political and economic implications.[16] The recovery of their ancestral lands is an important milestone in their history because it signifies a long-denied right and allows them to build their own political and territorial governance systems, based on their traditions, culture, forms of social organization, food and their own concept of development and good living.

However, the President of Costa Rica continues to make public statements offensive to Indigenous Peoples. At the start of the year, President Chaves described the Indigenous land recovery movement as a “minority group inclined towards violence against non-Indigenous occupants”. This statement was denounced as neocolonialist, discriminatory and racist by the Indigenous movement.[17]

Despite this, Indigenous Peoples continued to have successes and receive legal backing from the legislature. As in the previous year, rulings favouring Indigenous Peoples were forthcoming during 2023. In April, the First Chamber of the Supreme Court reiterated that the Guatuso Indigenous Reserve was the inalienable and non-transferable land of the Indigenous community. In August, that same chamber definitively resolved an appeal by a “bad faith” squatter who had lodged an appeal against the Maleku people in the Guatuso territory.[18] On 4 December, the “Court of Perez Zeledón acquitted an Indigenous family from Cabagra who were being sued by a non-Indigenous person”.[19] And, on 7 December, the Constitutional Court ruled in favour of the Bribri people of the Këköldi territory due to the failure to consult them during the drafting of the Coastal Regulatory Plan for Cahuita.[20] The court cancelled the public hearing at which the Municipality of Talamanca had presented its proposal and ordered that a new hearing take place, with due notice given to the Bribri people of Këköldi.[21]

Incompetence in initiating the regularization process in Indigenous territory

In February, INDER reported that it had invested 656.4 billion colones (EUR 1.14 million) in purchasing land and relocating “bad faith” squatters within Indigenous territories.[22] This is despite repeated resolutions from the Constitutional Chamber[23] making it clear that “bad faith” squatters must be evicted without compensation.[24] It is striking that, in 2022, the previous government left a fund of 3.2 billion colones (EUR 5.57 million) for the Indigenous Territories Recovery Plan, five times more than the amount that was announced in February 2023.[25],[26]

On 20 December, INDER paid 365 million colones (EUR 635,713) to a “good faith” squatter in the Conde Burica territory.[27] This event is historic because, after waiting more than four decades, the government has undertaken an initial (and highly consequential) compensation for the recovery of a non-controversial Indigenous territory.

Recognition of Indigenous knowledge in forestry governance

In a very positive development, the REDD+ mechanism[28] has finally recognized the importance of Indigenous knowledge in forest governance and its substantial contributions to solutions for climate resilience. The first payment of benefits under the Contract for the Reduction of Forest Emissions (CREF) mechanism was announced in two Indigenous territories: Talamanca Cabécar and Ujarrás.[29]

Impunity continues for the murderers of Indigenous leaders

Against a sociopolitical backdrop that fuels a climate of injustice and historical impunity for people who kill Indigenous individuals and environmentalists in Costa Rica,[30] 2023 began with a hope of justice for Indigenous Peoples, as the trial of Juan Eduardo Varela,[31] confessed murderer of Indigenous leader, Jehry Rivera, began on 23 January.[32] The crime occurred in the context of a land recovery campaign by the Brörán people of Térraba.[33] The court found Varela guilty of the murder, but he was sentenced to the minimum penalty of 22 years and 15 days in prison (20 for murder, 2 for illegal possession of a weapon and 15 days for threats), even though the Public Prosecutor's Office and the plaintiff had called for the maximum penalty of 35 years for aggravated murder.[34] This was in addition to another disappointment for the Indigenous movement when it was noted that the investigation had focused only on the hitman, with the intellectual authors of the murder remaining invisible to the prosecution. “State prosecutors do not see a connection between the violence against Indigenous leaders and their land rights activism.”[35] This hope of justice was again a fleeting illusion: in July, the Cartago Appeals Court issued a release order for Varela, after annulling the trial (due to a drafting error in the sentencing) and ordering a re-trial.[36] As the Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous Peoples stated during his last visit, “Impunity fosters a climate of violence and insecurity for the country's Indigenous Peoples.”[37]

It is also noteworthy that, eight years after the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights required precautionary measures from Costa Rica in order to guarantee the life and physical integrity of the Indigenous people living in Salitre, in May the Public Defender finally visited the Brörán and Bribri populations of the community.

Recognition of and tributes to two Indigenous women leaders

Bribri leader, pioneering land campaigner in Salitre, Mariana Delgado Morales Tubölwak, “Doña Mariana”, passed away on 3 January 2023. The Centre for Research in Culture and Development of the Universidad Estatal a Distancia published a compilation of the contributions and works of this outstanding community researcher and symbolic figure of Indigenous women's protagonism within the land recovery movement.[38] Another renowned Cabécar leader from China Kichá, Doris Ríos Ríos, received the International Women of Courage Award presented by the U.S. Government on 8 March at the White House. The award recognizes her exceptional courage, strength and leadership as a defender of the territory, a work for which she has received death threats.[39]

Dr. Bettina Durocher is an agricultural engineer with a Master's degree in rural development, a postgraduate degree in gender studies and a doctorate in education and intercultural mediation. She has conducted and published several studies on Indigenous livelihoods, socio-environmental conflict, agrarian rights and Indigenous women's knowledge of food security and forest conservation. She works as a freelance researcher and international consultant specializing in Indigenous women's rights and Indigenous forest governance, with an emphasis on Indigenous knowledge that fosters climate resilience. Contact: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

This article is part of the 38th edition of The Indigenous World, a yearly overview produced by IWGIA that serves to document and report on the developments Indigenous Peoples have experienced. The photo above is of an Indigenous man harvesting quinoa in Sunimarka, Peru. This photo was taken by Pablo Lasansky, and is the cover of The Indigenous World 2024 where this article is featured. Find The Indigenous World 2024 in full here

Notes and refrerences

[1] Calí Tzay, F. “Report of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, José Francisco Calí Tzay, on his visit to Costa Rica in December 2021.” Presented at the UN General Assembly on 28 September 2022. https://undocs.org/Home/Mobile?FinalSymbol=A%2FHRC%2F51%2F28%2FAdd.1&Language=E&DeviceType=Desktop&LangRequested=False

[2] Calí Tzay, F., “End-of-mission statement by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, José Francisco Calí Tzay, at the conclusion of his visit to Costa Rica.“ Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, 17 December 2021. https://www.ohchr.org/en/statements/2021/12/end-mission-statement-united-nations-special-rapporteur-rights-indigenous

[3] Calí Tzay, Francisco, Op. cit., p.3.

[4] Ministry of Justice and Peace (2023). “Se realizó el primer pago por indemnización a un ocupante de territorio indígena en Conde Burica.” 21 December 2023. https://mjp.go.cr/Comunicacion/Nota?nom=Se-realizo-el-primer-pago-por-indemnizacion-a-un-ocupante-de-territorio-indigena-en-Conte-Burica

[5] Ibidem, p.5.

[6] People (non-Indigenous) who acquired land within Indigenous territories prior to the 1977 Indian Act are called “good faith” squatters and are entitled to be expropriated with compensation from the State; those who purchased land within Indigenous territories after 1977 are considered “bad faith” squatters and must be evicted by the State without any monetary compensation.

[7] Vargas Mena, Emiliano. “Pueblos indígenas contemporáneos en Costa Rica: construyendo sus derechos.” Coord. editors: Maximiliano López, School of History, Universidad Nacional Heredia, Costa Rica, p.18, 2020.

[8] III Informe de agresiones y violaciones de los derechos humanos de los pueblos originarios de la Zona Sur; Pomareda García, Fabiola. “Tribunal de Pérez Zeledón absuelve a familia indígena recuperadora de Cabagra demandada por no indígena.” Semanario Universidad, 4 December 2023. https://semanariouniversidad.com/pais/tribunal-de-perez-zeledon-absuelve-a-la-familia-indigena-recuperadora-de-cabagra-demandada-por-no-indigena/

[9] Martínez, Alonso. “Gobierno espera reubicar propietarios de mala fe para ‘evitar el conflicto social’.” Delfino.cr., 20 February 2023. https://delfino.cr/2023/02/gobierno-prepara-terrenos-para-reubicar-a-propietarios-de-mala-fe-de-territorios-indigenas

[10] Drafted by Camacho Nassar, Carlos (2022) Source: Marcos Guevara Berger and Juan Carlos. Vargas (2000). “Perfil de los Pueblos Indígenas de Costa Rica.” San José, RUTA; Fergus MacKay y Alancay Morales Garro (2021). “Violaciones de los derechos territoriales de los pueblos indígenas. El ejemplo de Costa Rica.” Forest Peoples Programme. Verified with the National Commission for Indigenous Affairs (CONAI) in 2021.

[11] Approximate values, as there are differences depending on the sources consulted.

[12] Solís Aguilar, David, personal communication, 13 January 2024.

[13] Jordán, Eusebio. “Talamanca, somos un pueblo originario, un pueblo sin frontera.” Delfino.cr., 2023. https://delfino.cr/2023/08/talamanca-somos-un-pueblo-originario-un-pueblo-sin-fronteras

[14] Camacho Nassar, Carlos. “Costa Rica”. The Indigenous World 2010. IWGIA, 2011, 131-132.

[15] Muñoz Solano, Daniela. “Gobierno se compromete a iniciar proceso para otorgar territorio a indígenas Ngöbe en Sixaola.” Semanario Universitario, 31 March 2023. https://semanariouniversidad.com/pais/gobierno-se-compromete-a-iniciar-proceso-para-otorgar-territorio-a-indigenas-gnabe-de-sixaola/

[16] Pablo Sibar Sibar, personal communication, 28 November 2023 and Emilio Vargas Mena, personal communication, 7 January 2024.

[17] Martínez, Alonso. “Gobierno prepara terreno para reubicar ocupantes de mala fe para ’evitar el conflicto social’.” Delfino.cr., 20 February 2023. https://delfino.cr/2023/02/gobierno-prepara-terrenos-para-reubicar-a-propietarios-de-mala-fe-de-territorios-indigenas

[18] Chacón, Vinicio. “Sala 1: Integridad de territorios indígenas es inalienable, aun cuando no conste en Registro Nacional.” Semanario Universitario. 25 August 2023. https://semanariouniversidad.com/pais/sala-i-integridad-de-territorios-indigenas-es-inalienable-aun-cuando-no-conste-en-registro-nacional/

[19] Pomareda García, Fabiola. “Tribunal de Pérez Zeledón absuelve a familia indígena recuperadora de Cabagra demandada por no indígena.” Semanario Universidad. 4 December 2023. https://semanariouniversidad.com/pais/tribunal-de-perez-zeledon-absuelve-a-la-familia-indigena-recuperadora-de-cabagra-demandada-por-no-indigena/

[20] Sanche, Dulcelina. “Këköldi se opone al Plan Regulador de Cahuita.” Semanario Universitario. 31 July 2023.

https://semanariouniversidad.com/opinion/kekoldi-se-opone-al-plan-regulador-de-cahuita/

[21] Molina, Lucía. “Sala IV ordena consultar el Plan Regulador de Talamanca con ADI del territorio indígena Këköldi.” Semanario Universitario. 12 December 2023. https://semanariouniversidad.com/pais/sala-iv-ordena-consultar-el-plan-regulador-de-talamanca-con-adi-del-territorio-indigena-kekoldi/

[22] Martínez, Alonso. “Gobierno espera reubicar propietarios de mala fe para ‘evitar el conflicto social’.” Delfino.cr. 20 February 2023. https://delfino.cr/2023/02/gobierno-prepara-terrenos-para-reubicar-a-propietarios-de-mala-fe-de-territorios-indigenas

[23] Pomareda García, Fabiola. “Indígenas afirman que a la fecha no hay acciones concretas del Gobierno para reubicar a no indígenas que viven en sus territorios. Semanario Universitario. 13 September 2023. https://semanariouniversidad.com/pais/indigenas-afirman-que-a-la-fecha-no-hay-acciones-concretas-del-gobierno-para-reubicar-a-no-indigenas-que-viven-en-sus-territorios/

[24] Durocher, Bettina and Camacho Nassar, Carlos. “Costa Rica.” The Indigenous World 2023. IWGIA. https://www.iwgia.org/en/costa-rica/5084-iw-2023-costa-rica.htmls

[25] Martínez, Alonso. “Gobierno destina 3200 millones de colones para iniciar con la devolución de tierras en territorios indígenas.” Delfino.cr. 1 March 2022. https://delfino.cr/2022/03/gobierno-destina-3-200-millones-para-iniciar-con-la-devolucion-de-tierras-en-territorios-indigenas

[26] (sin autor). “Gobierno anuncia plan para regular territorios indígenas.” El País.cr. 17 February 2023. https://www.elpais.cr/2023/02/17/gobierno-anuncia-plan-para-regular-territorios-indigenas/

[27] Martínez, Alonso. “Gobierno destina 365 millones de colones a ocupante de territorio indígena y concreta la primera indemnización.” Delfino.cr. 20 December 2023. https://delfino.cr/2023/12/gobierno-destina-365-millones-a-ocupante-de-territorio-indigena-y-concreta-la-primera-indemnizacion

[28] REDD+: Reducción de las emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero debidas a la deforestación y degradación del bosque.

[29] MINAE. “Dos territorios recibirán más de 347 millones de colones por la reducción de emisiones forestales generadas en sus bosques.” 2023. https://www.minae.go.cr/noticias/2023/DECI%20075%20DOS%20TERRITORIOS%20INDIGENAS%20RECIBEN%20LOS%20PRIMEROS%20FONDOS%20POR%20%20LA%20REDUCCION%20DE%20EMISIONES%20FORESTALES%20GENERADAS%20EN%20SUS%20BOSQUES.aspx?s=08

[30] Chacón, Vinicio. “Representantes indígenas: Nada positivo nos ha dado Mesa Técnica establecida por Gobierno para tratar asuntos indígenas.” 27 January 2023. https://semanariouniversidad.com/pais/representantes-indigenas-nada-positivo-ha-dado-mesa-tecnica-establecida-por-gobierno-para-tratar-asuntos-indigenas/

[31] Chacón, Vinicio. “Es primordial que los territorios indígenas se limpien de la invasión de los no indígenas.” Semanario Universidad. 25 January 2023. https://semanariouniversidad.com/pais/es-primordial-que-los-territorios-indigenas-se-limpien-de-la-invasion-de-los-no-indigenas/

[32] Chacón, Vinicio. “Recuperación de tierras indígenas subyace en juicio por la violenta muerte de Jehry Rivera.” Semanario Universidad. 25 January 2023. https://semanariouniversidad.com/pais/recuperacion-de-tierras-indigenas-subyace-en-juicio-por-la-violenta-muerte-de-jehry-rivera/

[33] Durocher, Bettina and Camacho Nassar, Carlos. “Costa Rica.” The Indigenous World 2023. IWGIA. https://www.iwgia.org/en/costa-rica/5084-iw-2023-costa-rica.html

[34] Muñoz Solano, Daniela. “Allegados de Jehry Rivera se aferran a la esperanza de justicia luego que un tribunal condenara al sospechoso de matarlo.” Semanario Universitario. 18 July 2023. https://semanariouniversidad.com/pais/allegados-de-jehry-rivera-se-aferran-a-la-esperanza-de-justicia-luego-de-que-un-tribunal-condenara-al-sospechoso-de-matarlo/

[35] Brown, Kimberley. “Pablo Sibar y la lucha de los pueblos indígenas en Costa Rica por dejar de ser invisibles. Entrevista.” Mongabay.com, 2 March 2023. https://es.mongabay.com/2023/03/pueblos-indigenas-en-costa-rica-amenazados-entrevista/

[36] Muñoz Solano, Daniela. “Allegados de Jehry Rivera se aferran a la esperanza de justicia luego que un tribunal condenara al sospechoso de matarlo.” Semanario Universitario. 18 July 2023. https://semanariouniversidad.com/pais/allegados-de-jehry-rivera-se-aferran-a-la-esperanza-de-justicia-luego-de-que-un-tribunal-condenara-al-sospechoso-de-matarlo/

[37] Durocher, Bettina and Camacho Nassar, Carlos. “Costa Rica.” The Indigenous World 2023. IWGIA.

https://www.iwgia.org/en/costa-rica/5084-iw-2023-costa-rica.html

[38] Centre for Research in Culture and Development. “En defensa de la vida, pensamiento de Mariana Delgado Morales Tubölwak, lideresa bribri e investigadora comunitaria.” UNED, San José, Costa Rica, 2023.

[39] Mora, Andrea. “Estados Unidos entrega Premio Internacional Mujeres Valientes 2023 a indígena costarricense Doris Ríos.” Delfino.cr. 2023 https://delfino.cr/2023/03/estados-unidos-entrega-premio-internacional-mujeres-valientes-2023-a-indigena-costarricense-doris-rios

Tags: Land rights, Biodiversity, Conservation