The Indigenous World 2022: Colombia

Colombia is a country noted for its geographical, biological and cultural diversity. Vast coastal and Andean regions, tropical rainforests on the Pacific and in the north-western Amazon, the Orinoco plains, vast desert areas and islands are all home to 115 Indigenous Peoples and Afro-descendant communities, recognised as the collective subjects of rights by the Constitution and law.

According to the 2018 national census, the ethnic populations account for some 13.6% of the country's total population (of 48,258,494 people), there being 1,905,617 individuals who self-identify as belonging to one of the different native Indigenous Peoples. In addition, there are 4,671,160 Afro-descendant, Raizal, Palenquero and Roma people. Approximately 58.3% of the Indigenous population lives in 717 collectively-owned reserves, while 7.3% of the people belonging to Afro-descendant communities live in 178 collectively-owned territories, organised into Community Councils. Other than in the Amazon region, however, lands legalised as ethnic collective territories are few and far between, and while administrative and legal processes for the formation, expansion, regulation and return of ethnic territories slowed during the Alvaro Uribe administration, they have come to a standstill under the current presidency of Iván Duque.

This article is part of the 36th edition of The Indigenous World, a yearly overview produced by IWGIA that serves to document and report on the developments Indigenous Peoples have experienced. The photo above is of Indigenous Women standing up and taking the lead in the land rights struggle of their community in Jharkhand, India. This photo was taken by Signe Leth, and is the cover of the Indigenous World 2022 where the article is featured. Find The Indigenous World 2022 in full here

Indigenous Peoples on the front line of social protest

28 April 2021 marked the beginning of a memorable period in Colombia's recent history. For more than two months, the country witnessed a series of mass mobilisations and social protests unprecedented in the country’s history.

This social outburst, coming in the wake of smaller demonstrations in 2020, was triggered by the draconian tax measures that Iván Duque’s government intended to impose under the excuse of the COVID-19 crisis. Although these measures threatened to exacerbate poverty and widen the enormous inequalities from which the country has long been suffering, these protests were actually the result of an accumulation of economic, social, political and humanitarian difficulties that have been affecting most of Colombian society for decades, against a backdrop of drug trafficking and the internal armed conflict.

In 2021, town and city centres formed the main backdrop to the protests, and the severity of State repression and paramilitarism that has historically affected the most disadvantaged and vulnerable sectors in rural areas was thus revealed. This violence had previously been filtered out before reaching public opinion and the international community, under the banner of an endless heroic war on bandits, guerrillas and coca growers. This time, with the cities the direct scene of the State security forces’ disproportionate actions,[i] city dwellers themselves were able to witness live via social, community and academic media what was the main cause of massive human rights violations and the criminalisation of social protest. In this climate of State hostility towards those who took to the streets peacefully, there were dozens of murders, eye mutilations, sexual abuses, injuries, illegal detentions, hundreds of missing persons and even covert vandalism. In the space of just two months, more than 3,000 acts of aggression were recorded,[ii] most of them attributed to the security forces and armed civilians who were supporting the repressive police actions against youth and communities mobilised in the different cities.

This social uprising was undoubtedly the most significant event of 2021 and, indeed, in the country's recent history, and the ethnic communities and organisations –this time leaving their own territories to join the great demonstration– played an active role. Members of different Indigenous Peoples travelled from all corners of the country to cities such as Bogotá, Cali, Medellín, Pasto, Quibdó and Popayán to join the protest, demonstrating new forms of dialogue and interaction with the population. Indigenous guards offered their protection to protesters at rallies and during marches; shamans and wise men organised and carried out healing ceremonies and cultural celebrations; Indigenous women took the lead in community canteens to feed the protesters; and some Indigenous youth were at the forefront of tearing down statues and symbols of the colonisation, dispossession and plunder of the Colombian people while also participating in the erection of new representations of popular resistance and emancipation. In the words of the Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca (CRIC):

During this time, the minga [collective act of protest] set out to water and fertilise the seeds of struggle that were sown here. It did this by accompanying as many points of resistance as possible, to the sound of dance, flutes and drums. Distributing food in poor neighbourhoods, unmasking and revealing civilians and military who were infiltrating and vandalising the national strike. Opening humanitarian corridors for the supply of medicines, food and fuel. Teaching what the minga is all about and the ancestral forms of organisation and struggle.[iii]

The Indigenous movement’s capacity for mass peaceful mobilisation and its forms of resistance permeated the protests, generating new forms of mutual recognition, questioning secular forms of discrimination and exclusion, and establishing the Indigenous and Afro-descendant movement as a vital player in the processes of social, economic and political transformation and in the construction of peace as demanded by a majority of the country's population.

Unfortunately, the renewed empathy between Indigenous sectors and the general protesting population began to be painted in the regime's media as a threat against the “good people” of the cities, going so far as to offer justifications for the security forces’ and urban paramilitaries’ armed attacks against the mobilised Indigenous Peoples, especially in the cities of Cali, Popayán and Bogotá.[iv] This aggression continued over time despite appeals from various international human rights organisations such as the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR):

The Inter-American Commission rejects that several public statements were made over this period to stigmatise social protest and, especially, demonstrators from indigenous peoples and members of the social uprising known as Minga Indígena. In particular, the IACHR has been informed that groups of armed civilians indiscriminately shot against a demonstration of indigenous persons on May 9 in Cali. The IACHR deems the participation of armed civilians in acts of repression and attacks with firearms against demonstrators extremely serious.[v]

The consequence of these accusations from government officials and their allies[vi] was an open stigmatisation that was echoed in the most pro-war social sectors and media, resulting in an as yet unknown number of Indigenous people being attacked during the climax of the protests in different parts of the country. What is clear is that the joint attack by the security forces and armed civilians against the Indigenous Minga in the city of Cali was amply documented. The CRIC states:

More than 10 men and women from the minga suffered physical attacks at the hands of the police and their friends; some were dressed in black and others in white but both had pistols in their hands. We bore the brunt of the departmental and local media monopolies, which did nothing but point fingers, discriminate and stigmatise us.[vii]

For most of Colombia's Indigenous Peoples and ethnic communities, the 2021 protests against inequality, poverty, corruption, war and the cartelisation of political and economic power were merely a continuation of their historical struggles. However, their participation in them undoubtedly strengthened their relationships with urban populations, workers, students, traders, environmentalists, and others. Moreover, it contributed decisively to breaking the symbols and representations on which the elites and power groups have relied for centuries. The country thus entered an unprecedented period of transformation, and the Indigenous Peoples and ethnic communities became front-line protagonists, opening paths in the midst of diversity, setting an example in their forms of organisation, and positioning the changes that were coming in the collective imagination.

Prolongation of war and humanitarian crises

Most of the 24 early warnings issued by the Colombian Ombudsman's Office in 2021 to alert the authorities to the likely occurrence of acts of violence[viii] focused on threats to regions inhabited by Indigenous and Afro-descendant peoples and communities, especially the departments of Chocó, Antioquia, Cauca, Valle del Cauca, Nariño, Putumayo, Casanare and Vichada.

The analysis underlying the early warnings issued by the Ombudsman's Office generally indicates a reconfiguration of the risk scenarios created by illegal armed groups, who have never ceased operating in these regions and who remain in permanent dispute over control of territories, drug trafficking routes, trafficking of fuel and supplies for coca processing, illegal mining, arms trafficking, and support from corrupt politicians and governments, etc. The actors involved in this perpetual dispute are the so-called GAOMIL (Armed Groups Organised Outside of the Law), specifically guerrilla and narco-paramilitary factions.[ix]

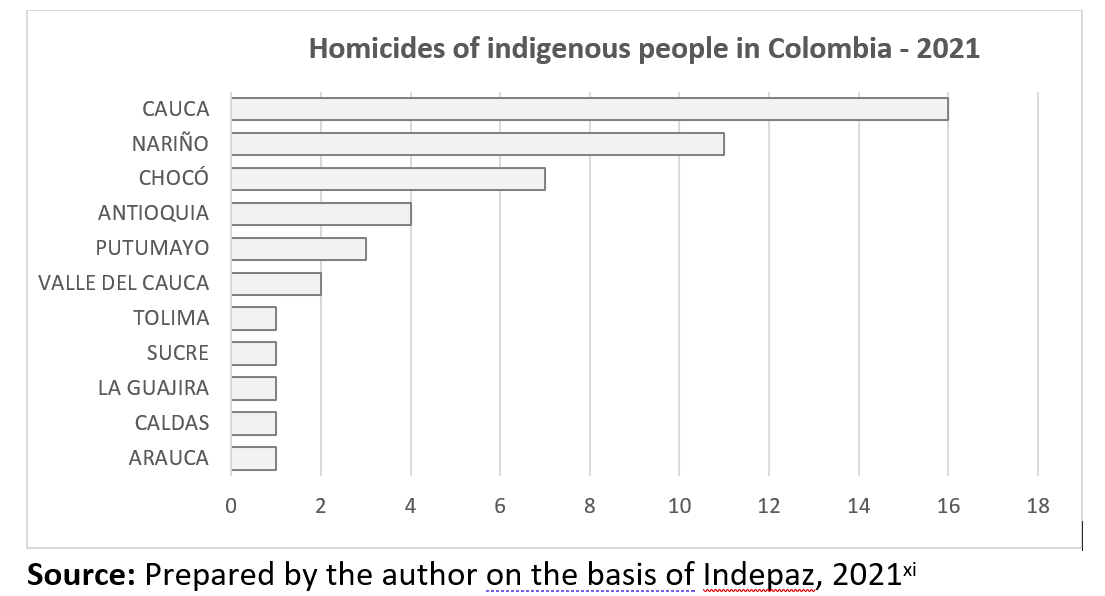

For its part, in its Third Report on the Human and Territorial Rights of Colombia’s Indigenous Peoples,[x] the National Indigenous Organisation of Colombia (ONIC) also indicated that the actions of illegal armed groups and the security forces entered a new spiral of violence and mass violations of individual and collective rights in 2021 in the form of territorial lockdowns of populations; mass forced displacements; harassment; and the forced recruitment of minors (with a significant 134 Indigenous recruits recorded). To these figures must be added the Indepaz report which states that, in 2021, 48 Indigenous people were murdered, most of them in the departments of Cauca, Nariño and Chocó, in other words, the western fringes of the country on the Pacific coast, disproportionately affecting the Embera, Wounaan, Nasa and Awá peoples and the traditional Afro-descendant communities living in their collective territories.

The Colombian government has given absolutely no response to the increasing violence in these territories. Despite the imminent risk alerts issued by the Ombudsman's Office, the communities have been completely abandoned to the aggression of these armed groups.

Finally, it should be emphasised that many of the ethnic territories with the highest rates of human rights violations and increased armed actions are located in the Pacific region of Chocó, in areas where large extractive and infrastructure projects are expected to be developed:

(In addition to the Tribugá Port) There is also talk of a series of unsustainable development projects that will affect life in this region. The Cupica Port in Solano Bay, the privatisation of the Atrato River, hydroelectric projects on the San Juan and Baudó rivers, and the construction of an inter-oceanic dry canal that would connect the Pacific and Caribbean by train, affecting the ecosystem and the communities that have defended the Darién territory for years. This plan is composed of a series of subprojects (...). In addition, palm monoculture linked to land dispossession, legal and illegal mega-mining, drug trafficking, arms trafficking, illegal logging and human trafficking. (Redepaz)[xii]

Indigenous women in the spotlight

Following the lockdown and their withdrawal from organisational dynamics as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, women from most of Colombia's ethnic peoples continued to consolidate their influence in community and territorial organisation and governance throughout 2021. The participation of Indigenous and Afro-descendant women continued to increase over the year, not only within the leadership of their own governments and regional and national organisations (governorship of municipalities, chiefdoms, councils, administrative positions) but also in the design and direct management of life plans and development projects in their territories.

Unfortunately, women’s entry into the political and administrative spheres of their communities ‒many of them victims of war, drug trafficking, extractivism and environmental degradation‒ has left them exposed to threats to their lives and integrity. April 2021, for example, saw the tragic assassination of Sandra Liliana Peña, a Nasa Indigenous woman and governor of her reserve in Cauca department.[xiii] The cause of the murder was directly related to her people’s decision to enforce its own law, protect its territory from environmental damage, and combat coca crops and drug trafficking corridors. Similar cases of threats against and murders of women defenders of ethnic territories have occurred in other parts of the country, highlighting the greater vulnerability of women who are involved in processes of self-government and in protecting their rights, territories and natural assets.

Another notable fact that corroborates the rise of women in social and political life, not only within their communities but in the country as a whole, was the appearance onto the national political scene of Francia Márquez and María Uriana Guariyú, the former a native of the ethnic territories of the northern department of Cauca and the latter an Indigenous Wayúu from La Guajira department.

These women, human and environmental rights activists in their territories, have opened up a political space of national importance and launched themselves as candidates for the Presidency of the Republic in the 2022 elections. The fact that these women are aspiring to power under equal conditions and capacities as other candidates is undoubtedly another sign of the profound political changes that are taking place within ethnic communities; however, it also represents a real challenge to the dominant and stagnant powers that are trying to maintain the status quo and their privilege by destroying the foundations of democracy.

The Raizal of San Andrés and Providencia in the eye of the hurricane

The archipelago of San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina in the Colombian Caribbean is the farthest island territory from the mainland. Most of its inhabitants are members of an Afro-Caribbean people that have their own language, culture and traditions, which is why they have been recognised by the Constitution and the law as the collective subjects of rights.

It is evident that the enormous geographical distance between the archipelago and the mainland has formed a protective barrier for the Raizal people and their culture but it has also resulted in their isolation and abandonment by the State, and this became starkly clear following the devastation caused by Hurricane Lota in November 2020.

This category 5 hurricane left 98% of the island destroyed, which is why President Iván Duque promised its reconstruction within 100 days. Throughout 2021, however, the Raizal people continued to suffer the effects of the disaster without any effective response, to the point that they decided to file for constitutional protection in order to put a halt to the massive violation of their rights to which the national government had condemned them, and to bring about the return to the islands of a large number of Raizal families who had been forced to migrate after the hurricane.

In this painful crisis for the archipelago, in which the disaster caused by the hurricane has added to the devastating impacts of a fall in tourism caused by the pandemic, the State must take urgent humanitarian measures to overcome the most vital challenges such as the provision of shelter, food, medicine and drinking water. (Dejusticia)[xiv]

Unfortunately, the rulings of the courts of first and second instance refused to protect the collective rights of the Raizal people, who are now awaiting a review by the Constitutional Court. Meanwhile, the Raizal people have a well-founded fear that the government's lack of attention and its intention to “relocate” the families affected by the hurricane to the mainland may be merely the continuation of a sinister plan of “Colombianisation” and exploitation of the islands without the uncomfortable presence of the Raizal people.

At that time, in the mid-20th century, there were plans on the part of the Colombian government to “move” the entire population of the islands to the coast near Barranquilla and recolonise the remote islands with population groups from the interior. This was to have concluded a complete Colombianisation and would have put an end forever to all arguments over the cultural and political independence of San Andrés and Providencia. The feared protests and the impracticality of such a move led them to abandon the plan in favour of a more subtle one.[xv]

Diana Alexandra Mendoza is a Colombian anthropologist with a Master's in Human Rights, Democracy and the Rule of Law. She is also a specialist in cultural management. She works with Indepaz and IWGIA as an independent researcher and has extensive experience in individual and collective rights, environment and culture.

This article is part of the 36th edition of The Indigenous World, a yearly overview produced by IWGIA that serves to document and report on the developments Indigenous Peoples have experienced. The photo above is of Indigenous Women standing up and taking the lead in the land rights struggle of their community in Jharkhand, India. This photo was taken by Signe Leth, and is the cover of the Indigenous World 2022 where the article is featured. Find The Indigenous World 2022 in full here

Notes and references

[i] Human Rights Watch. “Colombia: Egregious Police Abuses Against Protestors”. Human Rights Watch, June 9, 2021. https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/06/09/colombia-egregious-police-abuses-against-protesters

[ii] Indepaz and Temblores ONG. “Cifras de la Violencia en el Marco del Para Nacional 2021. Instituto de Estudios para el Desarrollo y la Paz. Junio de 2021. Registros del Observatorio de Conflictividades y DDHH de Indepaz y Temblores ONG. Junio de 2021. https://indepaz.org.co/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/3.-INFORME-VIOLENCIAS-EN-EL-MARCO-DEL-PARO-NACIONAL-2021.pdf

[iii] C.R.I.C. “¡Gracias Cali!” [Thank you, Cali!]. May 12, 2021. https://www.cric-colombia.org/portal/gracias-cali/

[iv] Torrado, Santiago. “Civiles armados disparan a grupos indígenas y el caos se apodera de Cali” [Armed civilians shoot at Indigenous groups and chaos reigns in Cali”]. El País Internacional,May 9, 2021. https://elpais.com/internacional/2021-05-10/civiles-armados-disparan-a-grupos-indigenas-y-el-caos-se-apodera-de-cali.html

[v] OAS: “IACHR Condemns Serious Human Rights Violations in the Protest Context in Colombia, Rejects All Forms of Violence, and Stresses that the State Must Comply with its International Obligations”. May 25, 2021. https://www.oas.org/en/iachr/jsForm/?File=/en/iachr/media_center/preleases/2021/137.asp

[vi] The government of Iván Duque managed to bring about a concentration of the different branches of public power and the oversight agencies, with the complicity of his party, the Centro Democrático, whose leader is Álvaro Uribe Vélez, and other allied parties of the moderate, radical and Christian right, such as the Conservative Party, Cambio Radical, Mira and Colombia Justa Libres. Representatives of these parties form the majority in the Congress of the Republic and occupy most of the high and medium-level public positions.

[vii] C.R.I-C. “¡Gracias Cali!” [Thank you, Cali!]. May 12, 2021. https://www.cric-colombia.org/portal/gracias-cali/

[viii] Ombudsman's Office, Delegate for Risk Prevention and Early Warning System. “Reports 2021”. https://alertastempranas.defensoria.gov.co/?page=1&anioBusqueda=2021

[ix] Among the main illegal groups active in the territories are the guerrillas of the National Liberation Army (ELN); the dissident factions of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) that did not take part in the Peace Agreement signed in 2016 with the government of Juan Manuel Santos; and the strengthened paramilitary groups that are part of the drug trafficking structures such as Sinaloa, La Mafia, the Gulf Clan (also called Autodefensas Gaitanistas/AGC, Los Urabeños or Clan Úsuga), Los Paisas, Los Boyacos, and others with local impact such as Los Shotas, Los Espartanos, among others.

[x] ONIC. . “Tercer Informe de la Organización Nacional Indigena de Colombia sobre Afectaciones a los Derechos Humanos y Territoriales en los Pueblos, Naciones y Comunidades Indígenas de Colombia 2021.” [Third Report on the Human and Territorial Rights of the Indigenous Peoples of Colombia]. November 18, 2021. https://www.onic.org.co/comunicados-onic/4407-tercer-informe-de-la-organizacion-nacional-indigena-de-colombia-sobre-afectaciones-a-los-derechos-humanos-y-territoriales-en-los-pueblos-naciones-y-comunidades-indigenas-de-colombia-2021

[xi] Indepaz. “Líderes Sociales, Defensores de DD.HH y Firmantes de Acuerdo Asesinados en 2021” [Social Leaders, HR Defenders and Agreement Signatories Murdered in 2021”. 14 November 14, 2021. https://indepaz.org.co/lideres-sociales-y-defensores-de-derechos-humanos-asesinados-en-2021/

[xii] Redepaz. “El puerto de Tribugá: genocidio, sometimiento y desarrollo nada sostenible.” [The port of Tribugá: genocide, subjugation and unsustainable development]. July 21, 2020. https://redepaz.org.co/el-puerto-de-tribuga-genocidio-sometimiento-y-desarrollo-nada-sostenible/

[xiii] Mendoza, Diana Alexandra. “El homicidio de una gobernadora indígena en Colombia: el límite en la resistencia del pueblo Nasa” [Murder of an Indigenous governor in Colombia: the limits of the Nasa people’s resistance]. Debates Indígenas, May 1, 2021. https://debatesindigenas.org/notas/104-homicidio-gobernadora-indigena-colombia.html

[xiv] Uprimny Yepes, Rodrigo. “Providencia y las tierras raizales.” [Providencia and Raizal Lands]. Dejusticia, November 23, 2020. https://www.dejusticia.org/column/providencia-y-las-tierras-raizales/

[xv] Somerson, Ruby Jay-Pang. “San Andrés, Providencia y Santa Catalina: huracanes, despojo y 'reubicación en Barranquilla'“. [San Andres, Providencia and Santa Catalina: hurricanes, dispossession and 'relocation to Barranquilla’]. Las 2 Orillas, November 25, 2020. https://www.las2orillas.co/san-andres-providencia-y-santa-catalina-huracanes-despojo-y-reubicacion-en-barranquilla/